Major Bagrat Sarkisovich Grikurov

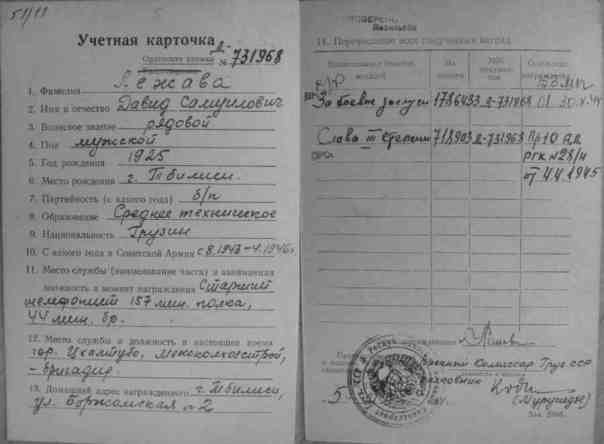

Private David Samuilovich Lezhava

When I received the research for Major Grikurov something unexpected happened – I recognized the unit and battle referenced in his award citation. Not from just any historical reading I’d done, but from another award group in my collection!

On the surface two individuals could hardly be more different. Grikurov was a Major, born in 1897, and had been in the Red Army since 1921. Lezhava, born in 1925, had been in the RKKA barely a year when he received his first award, and was a lowly Private. Grikurov was a “Propagandist of the brigade political department” and member of the Communist Party; Lezhava was a “Senior Telephone Operator” and a “non-party man.” Girukov was married; Lezhava was single.

But their files reveal that they served in the same outfit, the 10th Breakthrough Artillery Division, 44th Mortar Brigade. And they were both born in Tblisi, though Grikurov’s nationality is listed as Armenian while Lezhava was registered as a Georgian. This is significant in that they probably crossed paths because of their shared ethnic background. Grikov’s citation for his 5th award, the Order of the Patriotic War, 2nd Class, shows why:

In the capacity of the propagandist of the Political department of the brigade the prospective awardee properly organized the propaganda work, thus achieving a high political-moral status of the personnel, which ensured exemplary performance of battle tasks.

Fluent in languages of the Caucasian peoples, Comrade GRIKUROV succeeded in maintaining morale-and-welfare work among non-Russian soldiers in their mother tongues.

Comrade GRIKUROV spent most of the time in battlefield positions of the brigade units and gave practical assistance to the Party political workers and propagandists of the sub-units with morale-and-welfare work among the personnel.

In the period of stubborn fighting for KOENIGSBERG, PILLAU and the FRISCHNERUNG Spit, Comrade GRIKUROV was in the brigade sub-units, and his personal example of bravery, courage and his Bolshevist speeches inspired the personnel to successful completion of the battle task.

He deserves the government award, order of the Patriotic War, 2nd class.

Lezhava was drafted from his home in Tbilisi at age 18 in August, 1943. Odds are his native language was Georgian; as such he could have been one of millions in the Red Army who did not speak Russian. Often overlooked here in the west the Soviet Union was one of the most multi-ethnic countries in the world in the twentieth century, with only roughly half the population being ethnic Russians. By some counts there were upwards of two hundred different ethnic groups within the USSR, many with their own language. With the mobilization for war these groups were often thrown together in military units, and even if basic orders could be understood the isolation felt by non-Russian speakers in units where Russian was the primary language must have been severe. Hence the importance of officers such as Grikurov, and why his work would be seen as meriting an award of the level of the OPW.

As a soldier in the 44th Mortar Brigade Lezhava would likely have attended lectures and news readings by the political officers of the brigade. As a native Georgian he was probably known by Grikurov in his “morale-and-welfare work among the non-Russian soldiers.”

Private Lezhava’s job title is deceptive; as a Telephone Operator he did not sit at a switchboard, or in a dugout behind the lines, answering phones. His job is better described as “lineman.” He laid cable, probably burying it when time and terrain allowed, for field telephones. He was responsible for the infrastructure of the field telephone network that allowed the forward observers to communicate with the artillery and call in accurate fire.

The importance of cable to the Soviets (and other armies) in WWII cannot be overstated. We have the image of “walkie talkies” everywhere, with everyone in instant, clear, radio communication with “HQ.” This image is simply not true; wireless sets were expensive, bulky, and relatively fragile 60 years ago. When war broke out in the 1930s most militaries did not even include a radio in every tank – communication often took place by opening the hatch, sticking your head out and waving flags! As the war progressed the importance of communication in the new age of mechanized warfare became clear, and radios were in high demand. But the field telephone system was never made obsolete. It even had a couple of operational advantages over wireless besides being cheaper and sturdier; the enemy couldn’t easily “listen in,” and once lines were laid the system was very reliable. There was no question of which channel to use, losing the signal, interference, etc.

The biggest disadvantage of the field telephone system was its static nature. It had to be physically set up, and if the battle moved then it was often made irrelevant. But in the war in Russia this was less of an issue than is commonly thought. While the Blitzkrieg got all the press, most of the front for most of the time bore a striking resemblance to WWI trench lines. In that environment, on offense or defense, the field phone system was a natural fit. The defensive use is obvious – as the defender you lay down the wire to your front line and can thus instantly communicate with the rear, letting them know the true situation at the front, calling for reinforcements or calling in defensive fire. Offensively their use would seem more limited. But most offensives began as set piece affairs, with the attacker attempting to break through a built up line of defense, and in this environment the field phone was perfect. This was how the artillery was communicated with, as lines were run to the very edge of the front line and beyond to “forward observation posts.” There, brave individuals would see exactly what the artillery fire was doing to the defenses, and inform the batteries in the rear. These forward posts were in their turn prime targets, of course, as the enemy most definitely would NOT want someone directing large caliber shells onto their heads!

Of course what made the field telephone so cheap and reliable was also a weak point; wires can be cut. And the enemy would inevitably try to do just that, often with artillery fire. This was where Private Lezhava went to work. His two citations are both for repairing lines under fire. He won his Combat Service Medal in October of 1944 for repairing eight line breaks while under artillery fire. He won his Order of Glory in the attack on the fortifications surrounding Koenigsberg in January, 1945.

During fighting in East Prussian he has proven himself a bold and valorous communicator.

On 18 February of this year near Welau while under heavy artillery, mortar and small-arms fire, in the course of one day he repaired 30 telephone line breaks and during this, was wounded by shrapnel. Comrade Lezhava bandaged himself and did not leave the battlefield, continuing to accomplish his combat mission.

He is deserving of the Order of Glory III Class.

Welau was a fortified town in the line of fortifications to the east of Koenigsberg, so it makes sense that the 10th Breakthrough Artillery Division was used in the assault.

Private Lezhava’s group is also interesting from a collector’s point of view. Most striking is the date in the order book; it was issued in 1964, almost twenty years after the end of the war! The archives, however make it clear that the paperwork for his awards was processed in 1944 & 1945, it was simply never finished when the war ended (his award card bears the same date as the Order Book). What was the hold up? We’ll never know, but it’s a great illustration of the importance placed on GPW awards that the awards were distributed even decades late.

The second is the state of his CSM. When I acquired the group I kicked myself for a fool when I got it home – the CSM is a variation not made in 1944, when his was awarded! It looked like I’d been taken in (along with the seller – he’s a man of impeccable quality who always refunds if a problem is found), by a fraudulent group. In this case I thought someone took a later made CSM and stamped the serial number from the book on it, making the group “complete!” But some more research, and bouncing the pictures off other collectors on a forum, convinced me that that the CSM is legitimate. It’s a replacement for an award given in 1944 – a later type CSM, normally without serial number, that has been stamped with the serial number from the 1944 issue award.

The second is the state of his CSM. When I acquired the group I kicked myself for a fool when I got it home – the CSM is a variation not made in 1944, when his was awarded! It looked like I’d been taken in (along with the seller – he’s a man of impeccable quality who always refunds if a problem is found), by a fraudulent group. In this case I thought someone took a later made CSM and stamped the serial number from the book on it, making the group “complete!” But some more research, and bouncing the pictures off other collectors on a forum, convinced me that that the CSM is legitimate. It’s a replacement for an award given in 1944 – a later type CSM, normally without serial number, that has been stamped with the serial number from the 1944 issue award.

The inclusion of his Medal for the Capture of Koenigsberg, and it’s accompanying document, make the group complete. Unlike  serial numbered medals these had none, and were not entered in medal or order books. They did have an accompanying document, a bi-fold heavy stock document with its own serial number, where the medal is named and the recipients information entered in pen.

serial numbered medals these had none, and were not entered in medal or order books. They did have an accompanying document, a bi-fold heavy stock document with its own serial number, where the medal is named and the recipients information entered in pen.

Research returned show that these three awards were the sum total of his military awards, though two decades late in coming. The serendipity of finding one of Major Grikurov’s awards in my collection, and theorizing (reasonably I think!) that they actually knew each other, is one of those joys of collecting.